My lure for the supper club was cast in a sea of wonder at the Kahiki in Columbus, Ohio.

The Kahiki was one of the most remarkable restaurants I have seen.

I was a 7-year-old living in Columbus the first time I visited the Kahiki in 1962. Just like a Northwoods supper club it was a larger than life destination.

Cascading indoor waterfalls were framed by big tiki gods, “tropical” rain fell every half hour and war chants and steel drum rhythms spun through intimate bamboo dining huts. More than 1,000 tropical fish were featured in an aquarium along the huge east wall.

Just like many Northwoods supper clubs, the ambiance overshadowed the food. The Columbus Dispatch once wrote that the Kahiki “is one of the few restaurants in Columbus in which food can injure you.”

My father was a purchasing agent who had been transferred from Chicago to Columbus by Swift & Company. Founder Gustavus Swift began in Chicago’s Union Stockyards–and Swift was a purveyor to Midwest supper clubs.

Kahiki Friday night fish fry? Mahi-mahi almodine.

Saturday night prime rum! [Click on Supper Club recipes for the exclusive Kahiki Polynesian Spell drink recipe.]

Like a Midwest supper club, the Kahiki was an accessible escape into another world.

Like a Midwest supper club of the 1960s, the Kahiki had a live trio: The Beachcomber Trio mixed “Beyond the Reef” with Andre Previn’s “Like Young.” The Beachcomber Trio were led by woodwinds-pianist Marcel “Marsh” Padilla, who during World War II was lead saxophonist behind the bands of Judy Garland, Bing Crosby and Bob Hope. I have a live album they cut in 1965 and it is easy to hear the timeless chill backdrop of clinking cocktail glasses and waterfalls.

The Kahiki was built in 1961 and designed like a New Guinean war canoe. The roof peaked at 60 feet at the front of it’s A-frame. It was the nation’s first free-standing Polynesian restaurant. I recall talking to Chicago restauranteur Rich Melman about the Kahiki (which means “Sail to Tahiti”) and we concluded it would be cost prohibitive to build a detailed 20,000 square-foot restaurant like this today.

The centerpiece of the main dining hall was an 80-feet tall tiki goddess with bright red eyes and a fireplace for a mouth.

Who wouldn’t be impressed?

The Kahiki was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in in 1997. The federal government cited the Kahiki’s “rich Polynesian culture, architectural design and influence on national and local restaurant history.”

The honor didn’t stop the Kahiki from being torn down in 2000 to make way for a Walgreen’s. More than 500 Kahiki fans from as far away as London, Melbourne and San Francisco flew to Columbus for a farewell party hosted by Otto von Stroheim of “Tiki News.” I flew out with a dear Chicago editor friend who really enjoyed the make-your-own-won-ton-bar.

Meeting fun friends at Kahiki farewell party, 2000

A few weeks ago I was going through my father’s archives in the basement of the west suburban Chicago home we moved to in 1966 after we left Columbus.

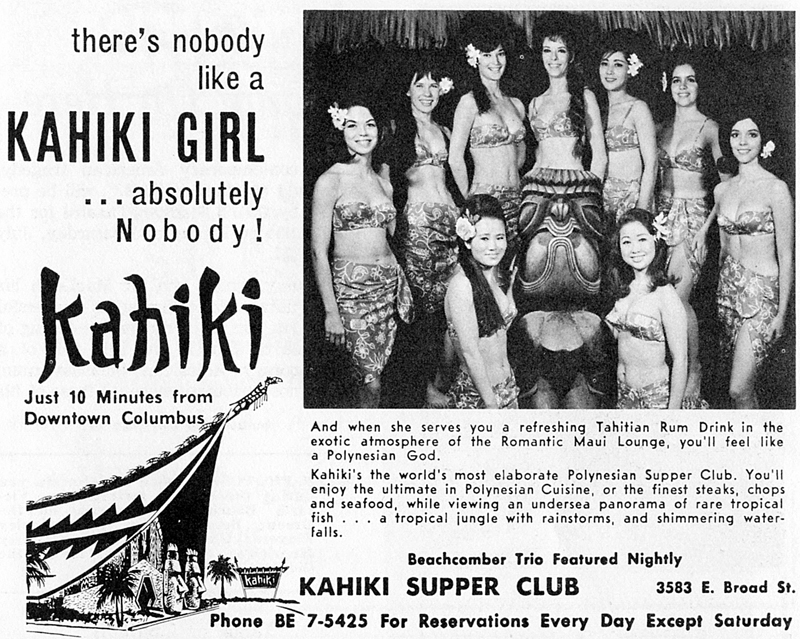

I saw an ad for the Kahiki in one of those weekly entertainment magazines you find in airports and hotel rooms.

I couldn’t believe my eyes:

“KAHIKI SUPPER CLUB,” just 10 minutes from downtown Columbus. (What made the Kahiki an even stranger destination is that the Polynesian supper club was in Bexley, the Jewish neighborhood where Chicago newspaperman Bob Greene grew up.)

The small print of the Kahiki Supper Club was a collision of cuisine: “Kahiki is the world’s most elaborate Polynesian Supper Club. You’ll enjoy the ultimate in Polynesian cuisine, or the finest steaks, chops and seafood, while viewing an undersea panorama of rare tropical fish…”

Note the quick transition out of Polynesian food in a meat and potatoes place like central Ohio.

But sense of place is the key component which connects the Kahiki Supper Club with Wally’s House of Embers (a Kahiki cousin in terms of crazy decor), Smoky’s Club in Madison or any others in my book.

I will never forget the Kahiki.

Life was larger, yet a bit more accessible.

Earlier this summer John Tierney wrote a fascinating New York Times piece about nostalgia as a positive emotion. University of Southampton (England) psychologist Constantine Sedikides had a conversation with a colleague, who was a clinical psychologist homesick for Chapel Hill, N.C. The North Carolinian assumed he was depressed because he was “living in the past.”

Sedikides countered, “Nostalgia made me feel that my life had roots and continuity. It made me feel good about myself and my relationships. It provided a texture to my life and gave me strength to go forward.” In the 14 years since that conversation Sedikides’ research on nostalgia has concluded in part that nostalgia can make people more generous to strangers and more tolerant to outsiders.

This is true of the warm feeling of a supper club. I hope to think I absorbed a bit of that as a kid in Columbus. Whether it replicates a large Polynesian canoe in Ohio or offers a majestic lake view in Wisconsin the American supper club creates an expansive canvas for vivid memories–even after the physical realm has gone away.

Not in Bexley. It was on the Columbus/ Whitehall border. Bexley was closer to downtown.